MY WRITING finds inspiration in a particular view of the world called process thought. Process thought is not a religion; it is a philosophy. But this philosophy is friendly to people of all faiths and traditions. In fact, this particular worldview, most identified with the work of mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, stirs one’s deepest spiritual inclinations, even for the irreligious. But, one might say, if I already have a religion—thank you, very much—then why do I need to think beyond that? Do we really need a philosophy or is it just so much head-talk?

We all have a philosophy-of-sorts going on in our heads at all times, whether we are conscious of it or not. Each of us comes to a religious text or tradition wearing philosophical glasses: certain assumptions we have about the world and about the people and animals that make it up. That’s why people who read the same sacred text can end up either a Pat Robertson or a Mother Theresa, a Hitler or a Martin Luther King, Jr. It’s all about what you bring to your religion: those hidden assumptions created by your cultural and psychological influences, your prejudices and traumas, your understanding of power and relationships and meaning. So, becoming aware of those assumptions that color our religion and the way we treat others and our planet is a good thing. That’s where philosophy comes in: it helps clarify our sense of meaning and our values. It helps us in our wondering, too. As Professor C. Robert Mesle says, “Philosophy is born of wonder; it is the art of wondering in a disciplined, thoughtful way.” Philosophy can even help us with our theology. After all, many of our theological assumptions come to us via the great philosophers of the past. Many of their ideas were good ones; others, not so much–or at least, severely outdated.

Take me for instance. During my seminary studies, I couldn’t get past the “problem of evil and suffering,” so my Christian faith took a reluctant and despondent nosedive into agnosticism. I could not, in good conscience, believe in God in the face of horrible realities like the Holocaust. After poring over all the traditional “theodicies” that tried to save a traditional God, i.e., an all-powerful, all-good God, my search finally came to a dead end. My spiritual life had become one huge sigh of regret. That’s when I took up the study of philosophy at the University of Missouri and became a teaching assistant. One day, as I was preparing to teach an Intro to philosophy class, one of my professors handed me a copy of a journal article by Charles Hartshorne about Whitehead’s view of God and the world. I devoured the article and signed up for a seminar on Whitehead. It was the beginning of my life-long love affair with process thought!

I was intrigued by Whitehead’s concept of a relational God which cut against the grain of the traditional view of God defined by Western philosophy (and duly adopted by Western theologians). In Whitehead’s philosophy, the all-powerful, supernatural ruler of the universe gives way to the relational, transforming “poet of the world.” The traditional Greek concept of “perfect power” as “unilateral power” was turned on its head in this cosmology. Relational, persuasive power takes center stage in Whitehead’s “philosophy of organism.” So, God began to make sense again, this time as one who “dwells in the tender elements in the world, which slowly and in quietness operate by love.” (Process and Reality, 343)

But God was only part my personal “Copernican Revolution.” Whitehead’s radically open and interconnected view of the universe–a monumental break from Cartesian dualism–also made sense to me in light of quantum science. Everything began to make sense– not just my relationship to God, but to the pelicans and the tree frogs and bees. I no longer had to choose between science and religion–what a relief!

Finally, after reading John Cobb, David Griffin, and Marjorie Hewitt Suchocki, three brilliant process theologians from the Whiteheadian tradition, I was able to return to my Christian roots—albeit with a radically fresh understanding of God and the world. I even became a minister and introduced my husband, a biblical scholar, to process thought. (He ended up writing a seminal work on process hermeneutics.)

But process thought is not just for Christians-in-crisis—not by a long shot. Some of the finest process theologians today are Jewish (e.g., Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson) and Muslim (e.g. Farhan Shah). Many traditions East and West are currently in dialogue with Whitehead–Buddhism for example, which, like process thought, has always been a relational, interconnected way of seeing the world. Buddhism makes sense in light of process thought–a great deal of sense. In China today, with its event-oriented language and rich philosophical history, Whitehead’s thought is blossoming. Process is big-tent philosophy for anyone of any faith — or naturalists, environmentalists, and those who have an understanding of spirituality that stands outside of any particular religious tradition.

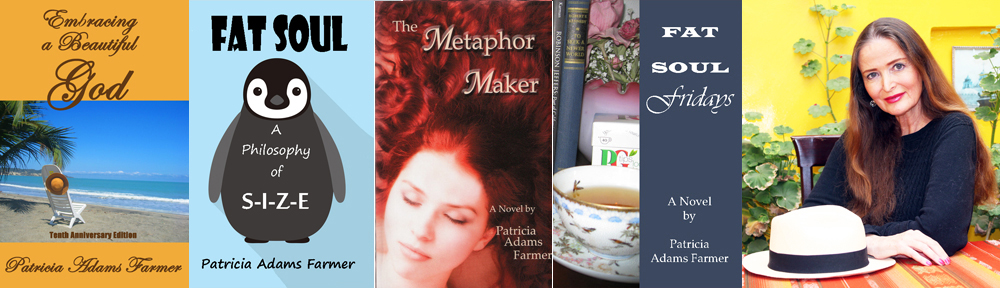

Process thought allows me to embrace my own tradition even while I deepen my appreciation for other spiritual paths. In a nutshell, process engenders empathy. So beware of becoming a process thinker! You will be infused with and challenged by empathy, and that changes everything. Heaven forbid, it might even change your life direction! It did mine. In fact, that’s why I love writing fiction: It allows me to get inside the skin of my characters. Characters who are unlike me. Characters with different views of the world, different religions, different hang-ups, different genders and sexual orientation. Yes, I want to feel with them and know them and present them to the world. This need to empathize in storytelling bubbles up not only from artistic passion, but because of process thought: a lovely luminosity in my life and soul.

For process thought is all about expanding our souls to embrace contrasts and differences in a richly interwoven world that is always in the process of becoming. It’s about seeking beauty in our relationships, not only with people who are different from us, but with animals and the planet and very air we breathe. And in this world of religious conflict and environmental disaster, such a philosophy as Whitehead’s—one which promotes beauty and justice and relational harmony among all living beings—well, it couldn’t hurt, could it?